A primer (part 1)

I’ve just run another course on Culture and auditing culture in London with 12 in attendance. This brief article gives a summary of key points concerning common misperceptions, and is offered as a counter-balance to much of what is currently being said about this topic. The second article will discuss specific approaches that, on my analysis, will lead to long-term progress in this arena.

Expectations of those attending

We discussed why people had come to the course and they said:

- “Our new company is defining its culture, so we want to input to that”;

- “We have many mergers and acquisitions and see culture issues as businesses try to merge, which we want to better understand”;

- “We know it’s important, and want to think about a culture audit universe”;

- “Auditing culture came up as an External Quality Assessment topic, so we want to learn about it”;

- “Senior stakeholders have been talking about it, so we wanted to know more”;

- “Our internal audits of risks point to root causes of issues coming from culture, so want to be clearer about what’s going on”;

- The remaining 6 attendees (50%) explained they had put a culture on their audit plan because it is a current hot topic, and now wanted to be clearer about how to do an audit.

Initial views on their organisational culture

I asked people if they had a word to say about the culture of their own organisation, or what the key challenges might be, that could be a focus of attention. Comments were:

- “I’ve noticed less professionalism in the organisation than where I worked before, less interest in documenting what’s being done, and think this creates a risk”;

- “I wonder whether management are talking enough about values and culture on a day to day basis”;

- “I sense there are micro-cultures and silos, and am sure this is harming effective risk management, especially across departments”;

- “I wonder whether some units in some countries are being open and transparent enough about their risks, issues and challenges – I sense not, but it’s hard to pin this down”;

- “Is there enough tone from the top about values and culture”;

- “New initiatives have been proposed on a diversity and inclusion, but are we really living this on a day to day basis, is it really part of our culture?”;

- “There is a lot of change going on, including people leaving, and I think people are becoming more defensive, and this is likely to be adversely impacting risk management”;

- The remaining attendees explained that they thought they would do work on whether “on the ground” managers and staff were living to the values and cultural priorities that had been set at the top; one said: “Is it all aligned?”

It’s important to pause for a second and note that often times people describe culture as “soft” and intangible, but you can tell from what is being said, that the observations and concerns have some real basis in reality, although there is clearly some complexity and subtlety going on.

Definitions of culture/risk culture

We talked about the many different definitions of culture, including the well-known: “Culture is the way we do things around here” and also the less well-known, but insightful, definition by Edgar Schein: “Culture is a pattern of shared basic assumptions learned by a group as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration (…) A product of joint learning.” We also spoke about definitions of risk culture, KPMG offering on of my favourite definitions: “It is the system of values and behaviours that shape .. [the] decisions .. of management and employees, even if they are not consciously weighing risks and benefits.” I like this definition because of its careful use of language, and the notion that organisations may do things unconsciously. I explained that there can be value in making some distinctions between culture generally and risk / compliance culture, but my experience is that these are inter-related – so to imagine a clear boundary, or wall, between culture and risk culture can actually limit important opportunities for insight.

Models of culture

I outlined the many models that have been developed to look at culture:

- Edward Hall’s High/Low context model that explaining differences between western and other cultures in terms of, inter alia, how explicit communication should be;

- Hostede’s 6 dimensions – also offering an international perspective on cultural differences;

- Gareth Morgan’s “Images of Organisation” offering a range of imaginative frameworks around how to think of organisations and their culture;

- The Graves model of cultural differences concerning leadership – Monarchial, Presidential, Barbarian etc. and,

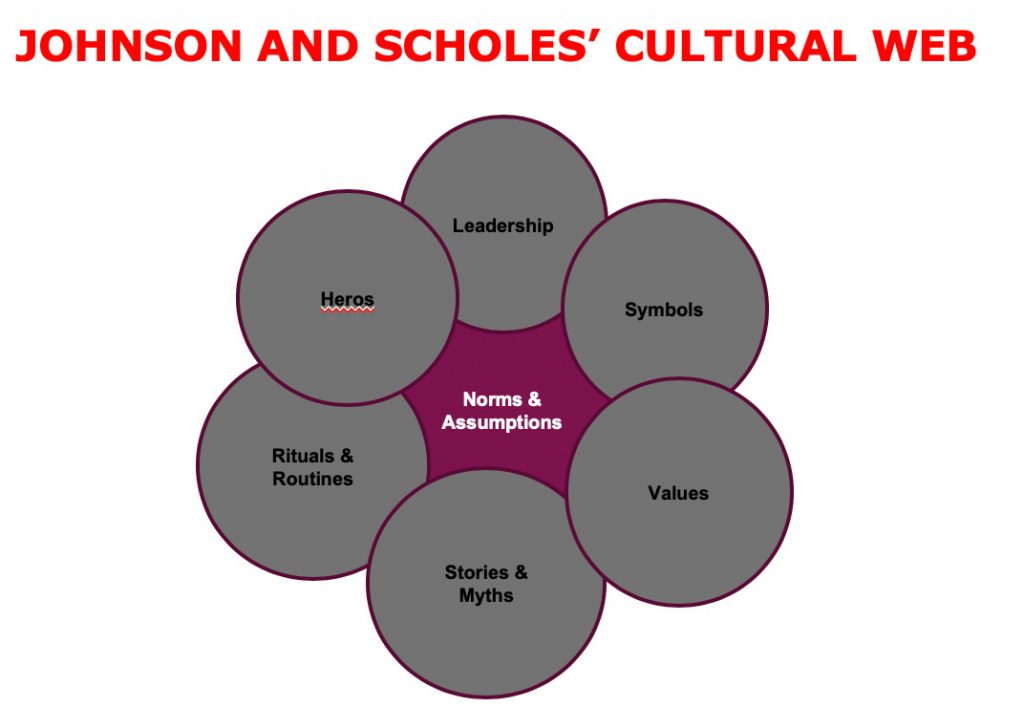

- The Johnson & Scholes cultural web, with dimensions including: norms and assumptions, heroes, symbols, stories and myths etc.

There are also many models in circulation concerning risk culture (e.g. from the IRM, FSB, the major consulting firms and also specialist HR consultancies). Most are slightly different from each other; and there is a nice research report “Risk Culture in Financial organisations” (M Power, S Ashby, T Palermo), where the similarities and differences between the models is set out in a table! My message to the workshop participants, and to you dear reader, is there is no definitive model for culture or risk culture; albeit that those from regulators are clearly important to understand. As I see it, each model offers perspective on what is important (some better than others), but none of them can “capture” fully what’s going on. Remember the wisdom of Alfred Korzybski: “The map is not the territory”; thus, view culture models as a way of “scanning” the patient (via X ray, or MRI scan etc.); but the patient is not fully represented by the X-ray, or image on the MRI scan.

Culture, sub-culture and behaviour

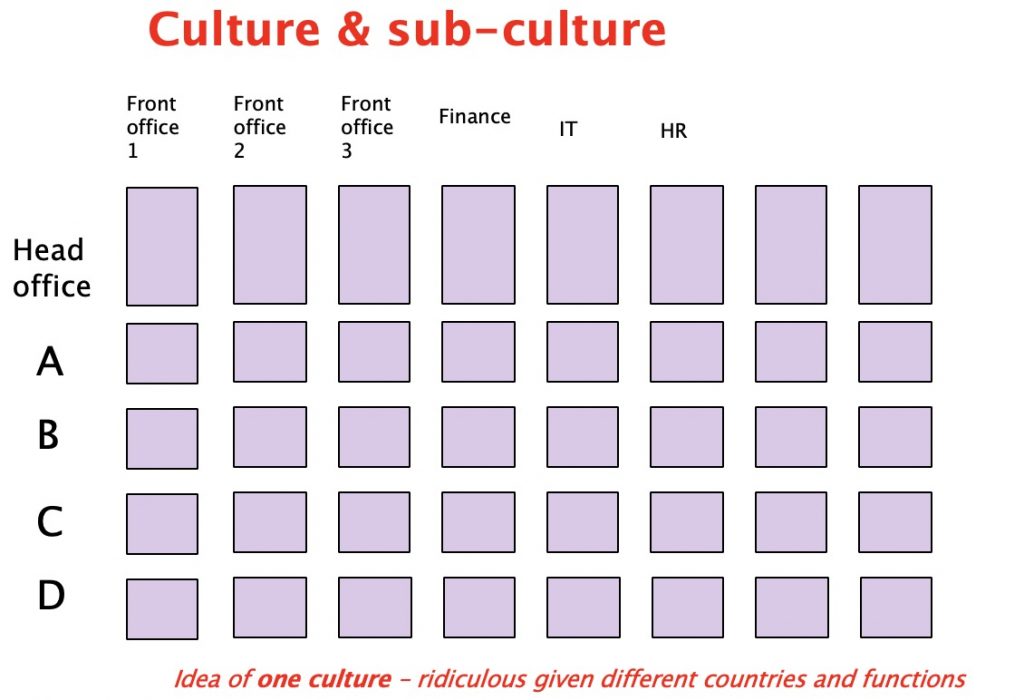

The next key message is to recognise the differences between:

- culture (the overall behavioural patterns that one might discern),

- sub-culture (the behaviours in a specific department, location etc.) and

- individual behaviours.

These differences are important because many speak about culture/people being the root cause of issues (e.g. the financial crisis). However, when you properly do a root cause analysis of issues that happen you will find it is a combination of specific practices and behaviours that actually cause each problem. In other words, culture is a short-hand for a range of behavioural and other problem areas that may be sensitive to name e.g. the design of incentive schemes, conflicts of interest and biases at a senior management level, and the way group dynamics and organisational politics impact business operations and decision-making.

We also spoke about the common view that culture comes from the “tone at the top”. This is partially true, but readers must be mindful of the difference between the “espoused culture and values” (e.g. what it says in the values statement and code of conduct) and the day-to-day attitudes behaviours of each and every leader and manager; which impacts the real culture. Sometimes, the impact of a middle manager can have a huge impact on the culture of a part of an organisation (i.e. the local sub-culture).

Then I hear people saying: “The problem with our culture is not about the tone at the top, it’s the tone in the middle”, but ask yourself whether may be more to it than that. Senior leaders are the bosses of the managers below them, and so on, so if middle managers are falling down could it be due to the fact that they are not being sufficiently monitored, and not getting sufficient coaching, support and resources to do the right things?!

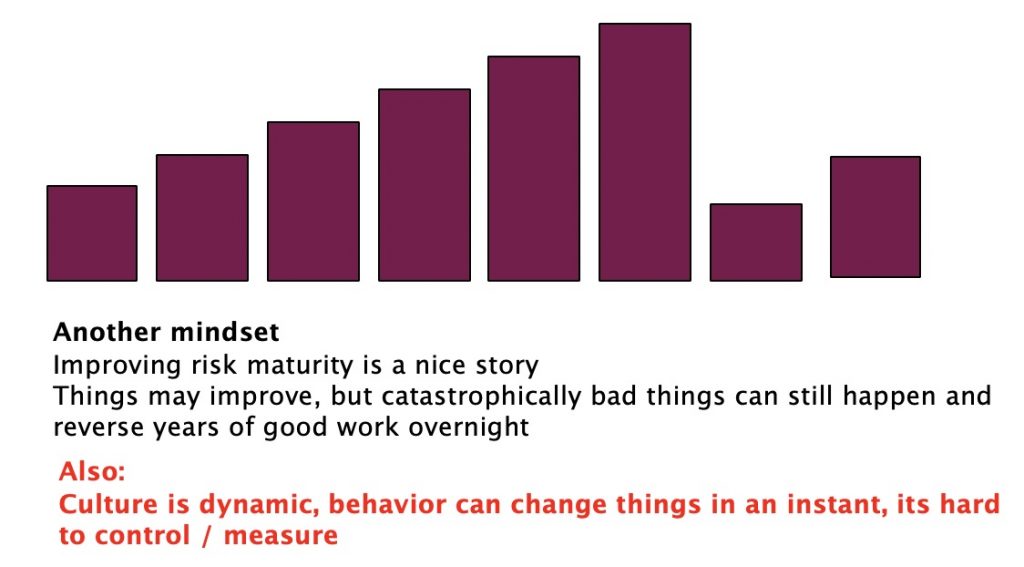

Culture is dynamic

Traditionally it’s easy to see culture as something that gradually develops and feel its “moving in the right direction”.

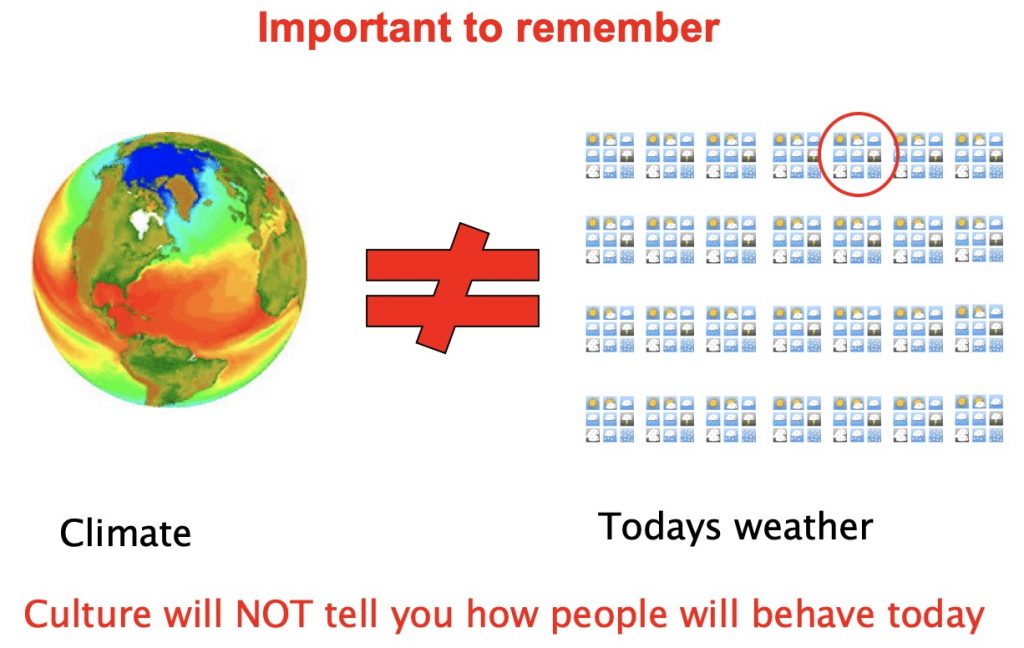

However, culture, sub-cultures and behaviour can be dynamic. You can think of the culture as you might think of the overall climate at this time of year, the sub-culture in terms of the climate in a specific part of the country at this time of year, and then behaviour like the weather today in a specific location. So, on average, its 15C and sunny with a few clouds at this time of year, but today as I write this article, its 10C and raining.

To give a more specific example: The risk culture in the IT function may be good generally, but tomorrow, when the Executive team are considering a new €20M IT investment, there may be some politics (e.g. lobbying, coalitions with finance and legal) to push through the decision that is actually riskier than may be appreciated, but then it’s largely “back to normal” the moment after the approval is given. In the next article we will explore further the notion that “Culture eats strategy for breakfast”, but recognise that bad behaviour may slip through a generally good culture in an instant!

Giving assurance on culture?

Given the dynamic nature of behaviour, is important to pay attention to when you think about the notion of giving assurance on culture – it may have no significant shelf-life! I fear it’s only a matter of time before one of the IA functions that has been providing assurance on risk culture is challenged when something bad happens in an area they said was OK. In fact, false assurance on culture may already have been uncovered, but how many audit teams would be prepared to publicize this to the rest of the internal audit profession?! I recognise, as a defense, we might say we only give “reasonable assurance”, but what does this mean if, in practice, a fundamental issue might slip through our hands? As I have written in my article on Corporate Governance theatre, I hope our profession will pay much more attention to the question of what reasonable assurance means in the future.

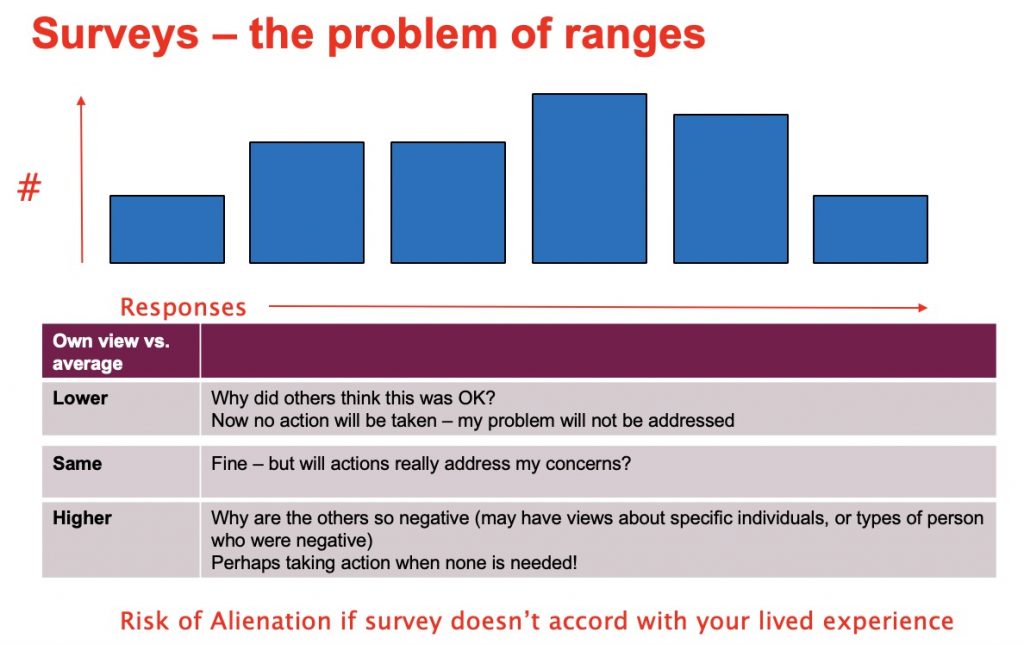

A word about surveys

It’s understandable that people associate culture with surveys about culture, but ask yourself the question who creates the culture survey, what questions are asked, and what questions are avoided? It’s not unusual to find important risk management behaviours are not always explored in much detail in a culture survey. Also bear in mind that individual survey responses will be based on perceptions (which may be biased in favour of most recent, or notable, memories) and – in any event – when reviewed in summary form, will comprise an average response rate of those surveyed. In addition, no culture survey will contain the opinions of any staff who haven’t responded to the survey, either accidentally, or deliberately!

The result of this is that you can analyze an employee survey and think: The big issue seems to be teamworking, but things seem to be fine when it comes to work/life balance; but miss the fact that, for example, an individual team member might be very over-worked and stressed, and therefore prone to taking short-cuts or making a mistake. From the team members personal perspective, they may see the survey results for their team and feel in minority and that no-one cares about their specific issue! In summary, whilst surveys have their place, it’s important to realise that surveys can easily gloss over detailed behavioural problems, and also alienate those whose views are not represented by the average.

Having worked in HR for several years, my big concern about surveys is that they can create a culture in which talking about survey results, and survey action plans, is used as a way of avoiding paying attention to the actual behaviour and culture that’s going on in front of you! A healthy culture is one where I can tell my boss that I need more support and help, and they will listen to that and work constructively on that in the here and now; rather than me waiting to put the fact that I don’t feel I’m getting enough support into a survey in 6-months’, and then waiting to see whether my feedback is acted upon!

The role of psychology in culture and behaviour

In the workshop on culture I walk through some of the fundamental psychological building blocks that impact human behaviour and, in turn, sub-cultures and culture:

- Self-justification – feeling good about what you have already done;

- Confirmation bias – looking for information that supports what you already think;

- Group dynamics – that affects the way people behave with others and also in committees and management team meetings;

- Perspective/Anchoring – which can make it hard to see something as equally important as another, due to your surroundings;

- Obedience to authority – where people are careful what they do/say when around authority figures (often tending to suppress negative messages).

These, and other psychological factors, are, in part, what can create unconscious biases in relation to gender, ethnic type; cultures of group think; silo thinking and may suppress the onward communication of issues, incidents and near misses and other important risk information.

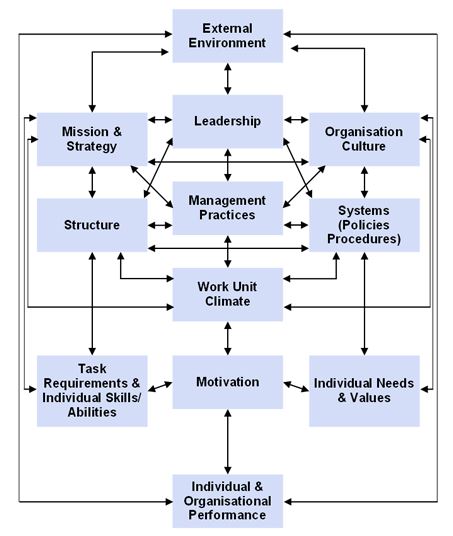

The role of systemic factors in culture and behaviour

In addition to this layer of complexity, sub-cultures will be affected by more tangible factors that are part of the way the organisation is set up and managed (so called “systemic” factors). Thus, if sales targets and bonus schemes are heavily slanted towards short-term delivery, sales behaviours, and in turn the sales sub-culture, will inevitably be inclined towards risk-taking. Other systemic factors will include organisation design and the way decision making processes are structured, including the way that the budgeting process works, how processes and policies and procedures are written and enforced and the approach to training and development etc. An excellent model to see the way systemic factors affect culture can be found in the Burke Litwin model, which I used as a culture analysis tool when I worked in Human Resources.

This model differs from most other culture models because it shows the way more systemic factors act as levers on the behaviour of persons in the organisation and in turn sub-cultures. It can act as a useful framework for thinking about root causes, and shows why it’s not always easy to manage and change a culture. You may carry-out training for staff on treating customers fairly, but if they are given stretch targets, and their bosses don’t want to know about the problems they face, then you have a classic example of a difference between the espoused culture and the actual lived culture experienced by staff.

Although I like the Burke Litwin model, lets remember it to is just a simplified way of diagnosing the patient, and others frameworks are available, such as the McKinsey 5S model and other “systems thinking” models.

In summary, as I see it, a proper way of understanding behaviour and culture in organisations – which combines psychological and organisational considerations, is the “systems psychodynamic” approach, pioneered by the Tavistock Institute of Human Relations. Their approach, and mine, is “model light” and starts by paying much more attention to the culture that is in front of you right here, right now, rather than what any survey results say. This approach also needs to include thinking about any expectations put upon internal audit, and the assumptions made by internal audit about what should be done and the best approach to adopt. In other words, you need to understand your internal audit culture before you can effectively analyze the culture of anyone else!!

Are we getting the whole truth and nothing but the truth?

You’ll read lots of people telling you they have “cracked” how to audit culture, they may have rolled-out a survey, run workshops (that were well received), and agreed improvement actions. In other words, it seems to me that the dominant culture in internal audit and associated consulting circles at the moment is that there is a best way to approach auditing culture, and if you follow this approach (and buy one of their culture models/surveys on offer, and employ their consultants), then all will be well!

I’m interested to hear about these stories, and have no doubt that some great stuff has been done, but my experience, the consulting assignments I have done, and the war stories I have heard, makes me wary of thinking that what might have worked in one organisation, at one time, in one context, will work equally in another organisation, at another time, with another context.

I recently read a “story” about auditing culture that is doing the rounds at the moment and noticed three interesting things: 1) It starts with a statement that both the CEO and Audit Committee want audit to do work on culture – when it my experience there are many instances when this is not the case; 2) It downplays existing work being done by HR, Risk and compliance in relation to behaviour and culture – when in my experience this can create a tension with what internal audit is going to do (“how is this joined up?”) and 3) It concludes with a presentation to the board about culture which the board found very interesting and would take away to decide what next – not mentioning any sensitivities or difficulties in the points being raised.

My concern is that there may be a tendency at the moment not to not share with you, dear readers, private reservations about short-comings in relation to work done on culture! It doesn’t make for good business, and it won’t help you win one of the awards for being an excellent audit function!

My take is that unless you really understand your organisations culture, its’ strengths and weaknesses and its key risks from a cultural and behavioural point of view, you can’t be sure what is the optimal way to make a contribution on culture in advance. To give a simple example: when it comes to surveys and focus groups, there are some organisations that have “survey fatigue” – so suggesting internal audit starts with a culture survey may not be regarded as an intelligent use of time and effort.

IIA standards to the rescue?

I think, when you think about culture and auditing culture from an internal audit point of view, it can help to go back to basics:

- We need to do risk- based audit plans (IPPF 2010) – so that means we need to be clear: is any cultural audit we plan to do actually going to reveal a key risk? Saying that some employees in some areas are not so motivated, or that others employees would like more training may be an interesting point, but what’s this got to do with the key risks the organisation faces?

- We need to have assignments that are aligned to strategies, objectives, risk and control processes (IPPF 2200) – even if we think that not having a compliance culture is a key risk, where exactly will be the areas of greatest concern, and what measures/controls (if any) are already in place to monitor/manage/control the behavioural/cultural risk? (This is why the notion of a culture/behavioural risk assurance universe is very interesting).

- We need to ensure clear, robust, criteria for any assignment (IPPF 2210), against which we can judge any facts obtained. So, if we are inclined to accept a culture framework adopted by management, how are we going to judge whether this framework is well designed? Second, if we want to propose an external framework (e.g. a model/questionnaire from a consultant), why would we choose one framework rather than another? If we choose a model that matches regulatory concerns what may be the other important areas that such a model does not address?

- Co-ordination and Assurance (2050) – we should share information, co-ordinate with, and consider relying upon other internal or external assurance providers; and note that line management assurance is included within this definition! So that means we need to understand how much we can rely on existing culture measurement and management processes before we start doing any audit work on culture.

Of course, there are standards around proficiency and evidence gathering that must be followed as well, and we will explore these issues, and other practical solutions to looking at behaviour and culture, in the next article.

Conclusions from those attending the culture workshop

Here is a summary of some of the key things that the participants on the culture workshop learned:

- I need to engage management, HR and risk in a discussion around roles & responsibilities for culture and how we are measuring and managing culture;

- I will weave more behavioural analysis into each assignment;

- I’m thinking now that instead of doing an audit of culture, we should do a more consultative piece of work;

- I’m starting to see the political aspects that surround any audit of culture – what do stakeholders want, what will they be sensitive about? And what would be the right name for any work we do in this arena?

- I won’t don’t want to bite off more than I can chew;

- I want to do more work on root cause analysis in my audit assignments, since I can see that better understanding of these will tell us about our culture / sub-cultures.

My summary message is that I hope internal audit readers will start to take enthusiastic accounts of marvellous things having been done in relation to culture with a more of a pinch of salt, and feel curious to learn more about culture, behaviour, psychology, systems thinking and root cause analysis. I also hope they will pay attention to, and explore, the culture of their internal audit team, and their organisation, before they jump in to a big culture audit.

Thank you for reading if you got this far!

Do e-mail me with any comments/questions at: info@RiskAI.co.uk

James Paterson, May 2019

James C Paterson started his career in finance and became Head of Group Financial reporting for AstraZeneca. He has a Masters’ degree in Management from McGill University and focused on organisational behaviour and culture. After that he became Head of Global Leadership Development programmes for AstraZeneca PLC, working on organisation and culture change. James was also Chief Audit Executive of the Group Internal Audit function of AstraZeneca for 7 years. James became a consultant, trainer and coach in 2010 allowing him to combine his interest in internal auditing with training and development. James runs training on auditing culture, root cause analysis, the politics for internal audit and a range of other courses for 12 of the IIA organisations in Europe, as well as on an in-house basis globally. James is the author of “Lean auditing”, published by J Wiley, which looks at how lean and agile ways of working can drive progressive ways of auditing, whilst maintaining and even improving added value and quality.

See www.RiskAI.co.uk for more articles and information, including testimonials and other training and development courses.